Nia Keturah Calhoun is Navigating the World of Art Without Compromise

The Artist Talks Ketanji Brown Jackson Mural, the D.C. Art Scene and More

DC is one of the most unique cities in the country in terms of its arts scene. You will see everything from street graffiti, and political art to fine art exhibitions and installations. Throughout each street, you will likely see a mural or sculpture of some kind, paying homage to history or just celebrating the rich culture of the city.

Nia Keturah Calhoun, is one of the constant contributors to this very scene. Nia is a multidisciplinary hailing from Maryland, who is constantly creating art that celebrates Black culture in America. If you have been in DC within the past few years, it's possible you have passed by her art without even knowing. She has recently created a cherry blossom sculpture that was acquired by the Mayor’s office, and sits within SE DC. She created visual artwork for Rare Essence’s Overnight Scenario detailing the famous scene the song plays out, and also painted some street dividers with a nice question on them, “What do they call math in DC? AD+MO.”

Recently, Nia was tasked with her first full mural. The subject? Supreme Court Justice nominee Ketanji Brown Jackson. By the time Nia finished the mural, the Senate officially voted to confirm Jackson and send her to join the court.

I caught up with Nia at the corner of 14th and S Street NW, in front of the mural to pick her brain about the mural making process, and how she approaches her art:

Introduce yourself to the people.

My name is Nia Calhoun. I am an artist. I grew up in Maryland. I'm now based in DC. I do a lot of things.I paint paintings, I paint murals, I'm a sculptor; but really I just come up with ideas that I think relate to the black experience and I try to figure out the best way to talk about them.

Okay, we are literally right here in front of your mural of Ketanji Brown Jackson, soon to be the newly appointed Supreme Court Justice. Her appointment was historical for obvious reasons, first black woman to the court. How did this mural come about?

There is this really really incredibly dope and important group of black women for black women who formed this organization called Sister SCOTUS, [Sister on the Supreme Court of the United States]. And for years they've been advocating, lobbying to get a black woman on the court because of a lot of reasons, one, Clarence Thomas has been on the court forever. And then before that we had Thurgood Marshall. But if you think about people who are deeply empathetic, who are really relatable, who will look at things from a lot of different sides, to me that almost embodies a black woman. So they've been advocating for a long time to get a black woman on the court and two years ago they did a mural to lobby and advocate to get a black Supreme Court Justice. When Kentanji Brown Jackson was nominated, they really started being like, okay, we have to do a mural to celebrate this, we've been going so hard for this for such a long time and they linked up with No Kings Collective, which is a great artist collective, they do a lot of things. They do like events in the city, it’s almost hard to tell you what they do. But they linked up with them like we need an artist; and I had been painting with them for about a year on their mural team and before that they had just been mentors for me for a long time. So they suggested me as a black woman who does murals in DC, that felt aligned, so I was very blessed to just be connected to the right folks to be able to do this and then celebrate the nomination and her and what it took for her to get there really.

When looking at the piece, what elements factored into what you included into it. Was watching the actual hearing a big part of it or was it just her nomination in general?

I think it's a little bit of both, right? Because I thought a lot about the history of who she was literally and figuratively. And so the whole style is like my attempt at AfriCOBRA art, which was a black arts movement that came out of Chicago in the sixties and seventies, and that was when she was born. So I thought it was really cool to look at the landscape that she would've stepped into as an American and what would've been black art when she was born. So I thought about her historically in that sense, but even on the mural, there's this little sketch of her and her dad at a kitchen table when he was studying for the bar, she would sit there and be in her coloring books when he would be studying his law journals.

So I just thought that that was really dope. I wanted it to be like her personal narrative, but also a larger narrative of black women in this country, which is why right below her is Constance Baker Motley, who was the first black woman to be a federal judge; and they share a birthday, which I think is crazy.

Oh, wow.

Super cool. And I'm almost embarrassed to say, but I didn't really know a lot about Constance Baker Motley before she mentioned her in her speeches and her confirmation hearing, but she was a baddie. She was the person who filed Brown vs. Board [of Education]. She was a clerk for Thurgood Marshall. She was a civil rights attorney who worked with MLK and just really put a lot on the line. She was the Manhattan Borough President, she was that girl, you know what I mean?

And I was like, wow, she's almost become lost in popular history and narrative which is really messed up. So I wanted to highlight both of those. But also watching the hearing, one of the things that stood out was just how ridiculous they were being and vile to this black woman, because of sexism and racism they felt like they were able to do that; and I realized when I was watching them that it hurts to break a glass ceiling to be the first of anything, like your head will get bloodied. So there's a lot of jagged shapes on here, a lot of sharp angles that represents her breaking through that. And lastly, I wanted to put in my thoughts about it. I think that it's really naive and disingenuous to think that just because we have the first of something that everything has changed because it hasn't. Racism still exists. Sexism still exists. All the systemic oppression that's going on in this country still exists right? Her nomination doesn't change that but it could be a sign for better things to come. Which is why there's a sun rising on this side and it's rising on her. I was like, oh yeah, like the Negro National Anthem, facing the rising sun, a new day's begun, let us march on.... so it's like yeah, it's a new day. Are we going to keep moving and grooving and doing what we can to make where we live and the communities that we live in better?

You mentioned a lot of the elements you pulled from and the symbolism you used within the piece. Was it emotional at all for you as a black woman to be tasked with this? Did you feel apprehensive about taking this on?

Wow, that's a great question. The answer is yes to those questions because you realize how many people have fought for this. How many women, like Constance Baker Motley, but also a whole lot of unnamed women who wish that they could have ascended to those heights and fought to ascend to those heights. For every law school, there is the first black woman who had to attend that law school, you know what I mean? I felt all that history when I was doing it and I wanted to do something that would specifically make black women proud. I wanted them to stop and take pictures of it. She's a justice for everybody but this mural is for black women and black girls.

It was also the first mural that I got to design by myself. I've worked on collaborative things before, but this is a hundred percent me. I had a great team of people who helped me put it up on the wall, but as far as it being my first mural, it's really my first solo mural. And so that also felt pressure cause I wanted it to be good because it was my first, I wanted black women to be proud of it and sometimes I would be freaking out on the wall. There was this one day, I think it was like the last day I was painting. I was up on the lift 30 feet in the sky and I looked out and there's this really cute black dad walking down the street holding the hand of this little girl who must have been like four and they just stopped. You could see that he was telling her who it was and she was smiling at this black girl who I'm sure looks like a lot of members of her family, myself on this lift, you know what I mean? And I was like, wow, that's who I'm doing it for. I shed a little thug tear but that was really special to me.

You talked about how you had a team of people helping you with this. I imagine you had an idea going into it but did any of your plans change once you started? Did you have to adapt once you started?

No. Making is just like problem solving

So just talk to me about that process of making a mural, working on such a big physical space.

Well, we're at an active construction site, so this awning wasn't here when we started, but it was here when we finished. So you're always trying to figure out safety for one, because you're on these big machines and then you have this sketch that's maybe a foot long in your hand and you're like, okay, I have to make this fit this 80 foot wall. And you're always trying to figure out the best way to make a round shape, or we couldn't physically get over there because there was this structure here. So how do we get 30 feet in the air when there's something right in our way? So there's always these little compromises and team huddles of okay, I think this is the best thing to do. Like, oh, okay, I see that for this, let's try this. But it really feels like one big project which is cool.

Speaking on murals in general, DC I would say, is a very visual city. If you drive through the city you'll see a lot of artwork, a lot of murals, a lot of physical art pieces. It really seems like the city tries to cater to that. What do you think of the overall art space here and how does it feel to be a contributor to that?

There was a huge barrier of entry that I was very blessed to have my hand held coming through it, which was really nice. But I remember being a younger artist and being one, confused, but two, frustrated and thinking I want to paint on walls. I want to put black people on walls around the city. How do I do that? Do I knock on the front door and be like, Hey, can I paint your wall?

I think it's beautiful because I do think public art is good for everybody. So I think the function of all these murals in the city are really, really cool. I'm very blessed to now be in community with a lot of people who are doing it, shout out to of course, No Kings Collectives, my big brothers and sisters. But besides them like Anikon oh my gosh, that man is like, to me, that man is like walking DC legend, black history. Like the fact that he had just put black people, but specifically black women all over this city is like crazy to me. I love his work. I think there's always this tension though, between kids who just have spray cans and muralists who are getting paid to do these walls.

Especially young kids like teenagers, like this kid I was talking to would probably really like to paint a mural as well, but the access points aren't there. So one of the things I really want to do as I grow and climb... I have a lot of young homies and I want to make sure that if they wanna paint a mural, they could figure out ,one, how to do it, but two, get paid for doing it. And then three, have there be a space for them to learn how to do it. Shout outs to Words, Beats and Life, because they have been doing that work for a long time.

Piggybacking on what you just said, can you speak to what it's like to be a young artist trying to navigate their way within this space in the area as well as general advice you would give to someone who's trying to navigate being an artist, getting into murals and things like that.

I think the thing that changed it for me was finding mentors and being like, I'm very serious. I am willing to run spray cans for you. Really kind of apprenticing with folks, but you have to come correct to do that, which is hard. And you have to be willing to put yourself out there, which is also hard. As an introvert, I didn't want do that for a long time, but the other avenues to do it, which is one, you know somebody who owns a building, and in a city that's rapidly gentrifying, and costs are rapidly increasing, the people who own buildings are usually not people who live in the community. So it's hard to just be a kid and know somebody who owns a building and has a wall. Or the other thing you do is you go through the city, but that also has barriers of access because you have to have experience most of the time to get those grants from the DC commission to do them.

So it's like when you apply for a job and they say you need work experience. You're like, how am I going to get work experience unless someone hires me. That's what it feels like trying to do your first mural in the city. But I think it's really figuring out who you like in the city and then sending them an email, or sending them a DM and being like hey, can I assist you on a mural one time, I would really love to learn how to do this. I'm really interested in getting into murals. What I've learned is people like Anikon, people like Keyonna from Congress Heights Art Center, they're so giving of themselves and the way that they really want to reach back and pull up, you know a high tide rises all ships, that love is in the city. You just got to work past feeling like everything isn't set up against you because I was definitely there for a long time. It was just like the barrier of entry is too high, I don't know how to do this.

So what is it like being a black artist and making very black culture specific pieces within a space that is as you mentioned, is rapidly gentrifying. Do you find more purpose in what you're doing because of those circumstances? Does it make you feel a certain type of way? How do you feel when you're producing art in a space like that?

It's really interesting because I'll get commission requests to do something where I feel like I would have to compromise on blackness and it's like, wow, like money is nice but I have to make art because I think it's so important. My dad is from East Capitol street and my mom is from Cherry Hill and Baltimore. Very black. Both of those places are very black and they made it a point having very black kids, to surround us in black art. And I'm still unpacking all the ways in which that was amazing for me growing up. But when I was working with young people in the city, I realized a lot of them hadn't had the same exposure to black visual artists that I had growing up. I mean my exposure was really, my parents had all the hood classics just hanging up. But I was just like, that's important. And I was used to seeing black people painted and how beautiful that was.

We've always been into art.

Always, black people have always been making art arguably better than anyone else, but I know that that's still important. So if I can be like how my parents were to me and put black people around this city… you know, 14th street five years ago did not look like us. Do you know what I mean? It didn't feel like this. And so sometimes I think it's an important reminder to just be like, we're here and we've always been here, and a lot of my art is reaching back to those connection points. I paint my former students a lot because I want to remind them always, I want them to be bold and audacious. This is your city and don't let anybody tell you different or make you feel like you don't belong where you belong, period. And that's for my kids who were at Ballou and that's for my kids who went to Duke. Both instances. These are your cities.

Being a multidisciplinary artist, you have different mediums that you work with. You mentioned sculpture work, painting, graphic and digital. How do you cater to all of those mediums? Do you feel a certain way and you'll lean towards one medium? When you're inspired by some art, how do you determine which avenue you'll take to explore or express that?

I think it's like what gets the idea across best? So for a few years I was doing this project when I was trying to make a fake FUBU alternate reality. Like what if FUBU made everything for black people? Like cell phones by FUBU, and products that would like... spray that got rid of Karen's, like FUBU you could really do anything with. And I'm like, what's the best way for me to talk about this; there should be a helpline. So I made a helpline where you could call this 1-877 number and there was an audio recording. And just figuring out different ways to make art that is so fun. So sometimes it's like a painting and I'm like, yeah that shows enough. But a lot of times it's just like no, I have to make this move, so I'll do an animation for it instead. But the best projects are the projects that I can do a little bit of everything with. But it's really just about what I think will best represent the idea.

Is there usually a different approach when you do something bigger versus like this mural, versus doing something that's smaller in size, such as the cherry blossom sculpture or the ADMO painting?

The approaches are really the same. Everything just starts with a sketch. When I started doing this mural it was a real quick turnaround. I had maybe a week to get this design done. Usually you have months when you're just planning a mural to figure it out and you go back and forth with the client. But because I had a week, it was like, okay, I had to do it. So at one point I was just sitting with my big brother, Brandon Hill, one half of the founders of No Kings Collectives in the middle of The Line Hotel. It was just us with sketchbooks, just like okay, think about this, think about that. And that's how everything starts. Animations will start that way. Sculptures will start that way, which I think is really beautiful because you realize that leven the biggest things start with just this little idea and anybody is capable of that first step. With Google, you can figure out the rest of the steps.

When I was teaching, a lot of my kids would get so intimidated because they would have these big ideas in their head. I'm like, it doesn't matter how big the idea is, you just need a little piece of blank paper and that's where every idea is going to start. So the process is really similar for all the projects.

You've mentioned teaching a few times, how much does working with students inspire you?

I miss it. I stopped doing it at the end of 2020 and just started doing art full time. But I was just telling my homegirl the other day I need to find young people again because I think my favorite artists have always been phenomenal because they've surrounded themselves with young people.

I have this great friend, Monie Shade. Genius girl. And she has this book called Things We Found so far, and one of the things she says in the book is sometimes your mentors will be younger than you. And I think teaching, yeah I'm able to put them onto things that I know, but they do the same thing for me. They're like, you need to listen to this or the way they think about the world even, because their generation is different from mine and more progressive. And they've had access to all of the answers since they were kids with Google. I remember learning about Google. These niggas have always known that you could ask the internet questions and it will give you,maybe not the answer, but an answer, which is crazy.

I mean my favorite artists surround themselves with younger people. If you look at 3k (Andre 3,000) and Erykah (Erykah Badu), I think they've had long careers where they've been so relevant for so long because they were always showing love to younger artists and being like, that's dope I'm going to see how that hits and I'm going to try that too. Erykah has a song with SZA you know what I mean? Before SZA was SZA she had a song with Erykah. So I think all that is really fire and I think everyone who's interested in mentorship should figure out a way to get into it.

So are you optimistic about the art scene in DC from your experiences with working with younger people or what you see or witness being in the art community?

I'm cautiously optimistic because DC as a city just has a really great culture and a super crazy history of art, period. Furthermore, to zoom out the District of Columbia, the DMV in general, like the first black art show was at the University of Maryland. So there's this crazy history of black arts in this city and in the surrounding areas and that's not going away no matter who comes in or how high the rent is, the city will have amazing black art in it because Washingtonians are just mad resilient, and they'll figure out a way to make their art.

I'm cautiously optimistic because it is becoming harder to do certain things, right? One of those things is maintaining art spaces. You keep calling me a young artist, but I'm not that young, but that's okay.

**laughs**

But when I first came home from Spelman 10 years ago there would be all these underground hip hop shows. Like Bombay Nas and I mean, before that growing up, there was always a go-go that was Metro accessible that you could get to; and the disappearance of those things are really concerning. It's such a big part of our history, our culture and our joy that I think there has to be a focus on maintaining it and preserving it and celebrating it for sure. Shout out to Yaddiya and Moechella right? But we got to make sure we hold space for young people to come through and do art, and feel free and not have a lot of parameters and those spaces dried up. If I was 20 something and I wanted to do an art show, I don't know where I would go do it.

I don't know where that would be and that's a problem because when I was 20, there were a whole bunch of kids who were like, yeah there's this yoga studio and we're going to go take it over. And I want there to be more spaces like that in the city. And there are certainly people who are doing that work, once again shoutout to Keyonna, Congress Heights Center, Black Swan Academy, the way that they lift up young black artists, young black students, they're definitely doing that work. But even certain institutions like Eaton hotel have really partnered with a lot of orgs. There are definitely people doing the work and we got to put our support behind them and get them more support financially and otherwise so they can keep doing that.

I have this notion or theory that DC as of recently now loves black art, the aesthetic of it. They love to sell that to people without actually putting support into the actual artists or the actual people who create that culture that they then sell to people. Do you agree with that sentiment? I don't think there are alot of physical art spaces that people can go to, yet I still see a lot of art initiatives in the city. What do you think about that contradiction?

Oh man.

**laughs**

I mean it's bullshit, right? The black aesthetic I think is people something that people really like. I was recently told, 'Hey, we really like your mural, it's super black. Could you do that, plus like maybe more white.' And I was like, what? What does that mean?

I mean the rent is too high. I do all my work in the city and I still can't really afford to be here, which is crazy, and I'm doing okay you know? So to think about younger people who are trying to come here and once again, younger people will always drive culture so if there's not a space for them to be, places where they can even hang out and eat for a reasonable price. If we're not cultivating spaces where artists can come to chill and connect with.... like I remember being younger and the Durkle store was just the spot. You would just go in there, meet so many people. Same thing with Commonwealth.

That's a throwback.

Come on for real. Like that's where I first met, like Scooty and Modi, you know what I mean? And people who I really still to this day look up to. But we were able to meet because there were these places... and there are definitely things like SOMEWHERE, shoutout to Dom, and Maketto definitely exists, right? And they definitely do work to make those spaces feel homey. But I definitely used to take my students in certain spaces and they felt like they didn't belong there. I'm like once again, this your city, you belong in these spaces. Don't let people tell you otherwise. So I really would love to see people putting more money into that.

You know what it's giving, do you watch Atlanta?

What's it giving? I do watch Atlanta.

Did you see that episode? It wasn't the most recent, but it was the one before that, with the fashion house?

Yeah, when the white fashion house accidentally made a t-shirt referencing the Central Park Five and had the fake initiatives to give back in order to ‘make up’ for that.

That's what it's giving. I'm like, where is this money going? What are we doing with this?

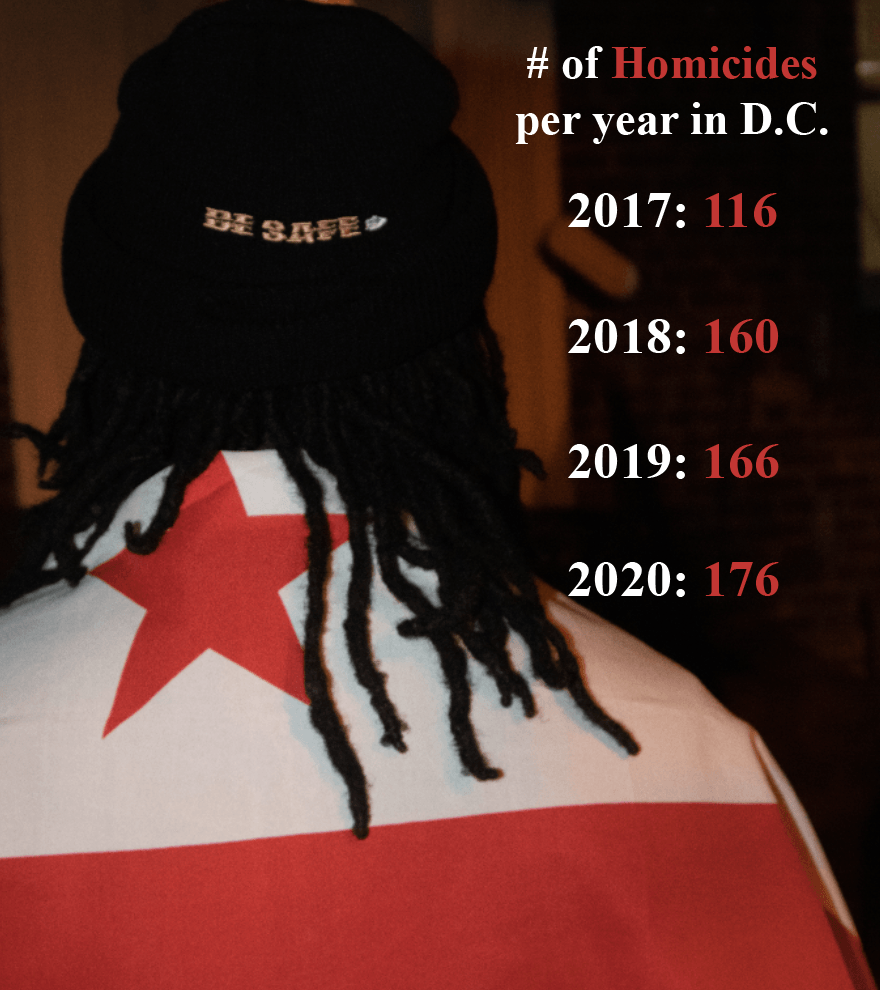

We got to do some thoughtful planning because what I don't want to happen here is.... what happened to San Francisco when they really became a tech hub... San Francisco has a lot of great culture. The bay area is where the Panthers got started, psychedelic movement, think about Jimmy Hendrx, it just has this crazy rich history. But the normal person can't live in San Francisco anymore. So the reason why people wanted to flock there, this wonderful culture is now like a copy and paste young white millennial city because those are the people who can afford to live there. So I don't want that to happen to DC where it's just like, yeah people want to come here because we have this great culture. We have this great music in Gogo. We have this amazing history and flavors. I mean, we've been here for how many seconds and we've met so many characters just shouting across the street. I want generations to come and to feel like this, and that takes thoughtful planning, that takes a mayoral office that really cares.

Actually cares.

Yeah, actually cares. So yeah man, I definitely don't have the answer, just a lot of questions.

You mentioned people will reach out to you and they'll love the work you do because it's very black. But some people might come to you and want you to do something that's more vanilla or compromises the things you believe in. How do you as an artist navigate that?

I just be ghosting people. I'm still working on the power of no and being like absolutely not.

So you don't compromise.

No. What I will do is, I will collaborate. So if someone has a legitimate thing and the people who I'm about to work with, they're like yeah we want it to reflect the whole community. I'm like you know that's supposed to be black. They're like, hey but maybe a couple other folks? I'm like, all right, maybe, you know what I mean? I love collaboration and I love creative abrasion where we're fighting to make our ideas happen in the best way that they can happen. I'm always down for that. But compromising who I am, what I believe in, like that's the hard no.

So recently, you know Nelly's went through it because they thought it was a good idea to drag a black woman down a set of stairs. Like wow, how dumb are you? To be honest, as a black woman, I just always never really fucked with Nelly's to begin with so it was never really a thing for me. But the artist who has the mural on the side of Nelly's, the ducks, it got defaced and now it's smudgy. She was like, will you redo it with me? I feel like it's just so important. I'm like, you know, I'm gay and sometimes I date girls and you're trying to use me and my blackness right? You want me to redo this mural with you so it can be a getaway pass for you to do it.

Like in Atlanta.

Like in Atlanta. **laughs** I told her absolutely not and I directed her to some organization she needed to talk to about why maybe she shouldn't redo it either. And then the same thing, another white artist came to me recently and said "hey, we should collaborate on this black lives matter project." I'm like what do you have to say about that? Do you have an interesting view? What I love and what I really fuck with No Kings for, this organization collected, founded by a black man and an Asian man is they know when to throw the alley oop to someone else, which I really love. That's very important.

So when they did the night market, they found Asian artists to do the art. I'm like, that makes sense, it's an Asian event, y'all should find Asian artists. And when they needed someone to do the Ketanji Brown mural, they're like, it needs to be a black woman. They’re like it shouldn't be us, but a lot of people don't wanna throw that alley oop. I'm like why would I collaborate with you for black lives matter? That's not making sense. Throw the oop. So a lot of times it's just like no, and you don't really care about black lives mattering, you just care about a bag and the perception of you caring.

You're always on alert to bullshit?

You got to keep your third eye open, they will really play you in these streets and have you looking crazy. I'm very blessed to have very thorough group chats, a lot of real niggas surround me and because a lot of real niggas surround me, I think there's this barometer of no. Because if my friends knew the situation, they would drag me and a lot of times when we see people mess up, it's like damn you don't have any real niggas around you, I can tell because you're out here wildin. Shoutout to Kanye, who I just feel like needs four real niggas around him, shoutout to him somehow.