Yaytunde Speaks: Expressing Artistry in Tumultuous Times

from our PACK Express project...

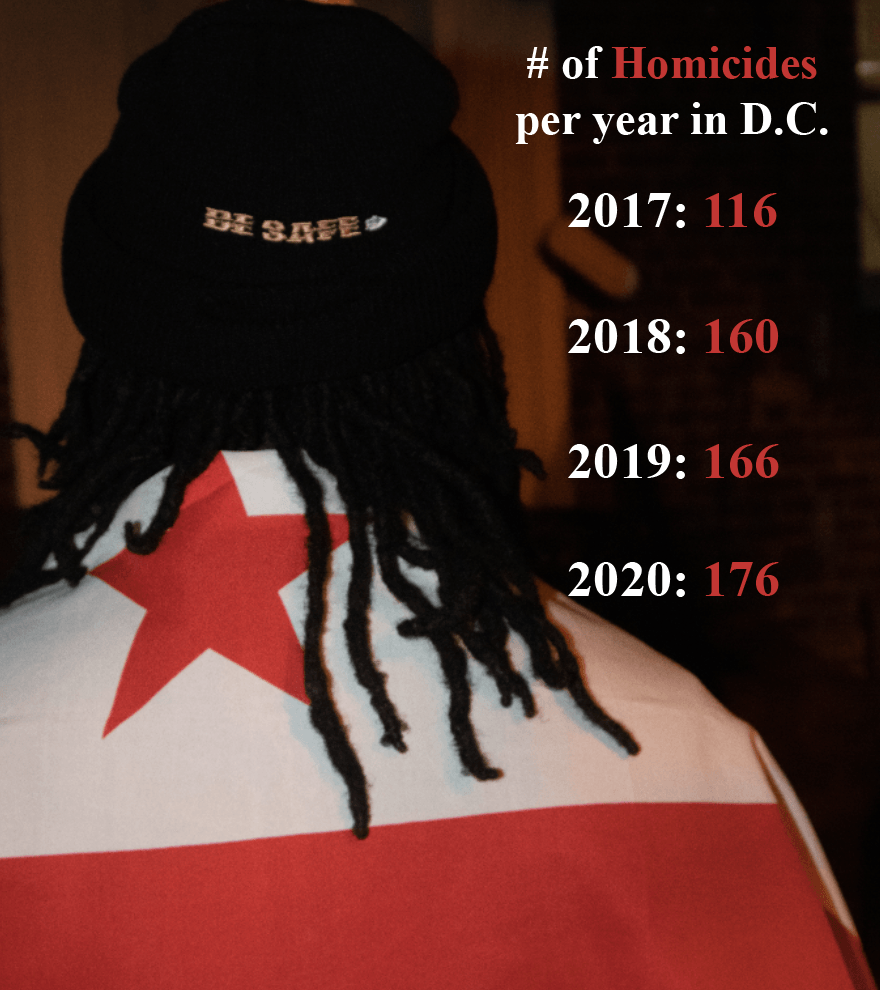

On May 25th, 2020, George Floyd was murdered by police officer Derek Chauvin, when he held his knee on Floyd’s neck for eight minutes and forty-six seconds. Video of Floyd’s last moments were recorded, and ultimately went viral through social media, sparking instant outrage. Subsequently, protests began nationwide, and the conversation on race and injustice in America was sparked once again. For many young Black Americans, Floyd’s death was the last straw. The tragic cases of Ahmaud Arbery as well as Breonna Taylor were already weighing on the minds of many. This was insult to injury. It was also nothing new. Each year, the list of black people who are murdered at the hands of the police grows. Many of those cases conclude with officers not being held accountable for their actions. In June 2020, we saw a boiling point nationwide. Despite the COVID-19 pandemic prompting the shutdown of business and life as we know it, protestors of all ages took to the streets. Many, looking for an outlet. A way to grieve and sort through the familiar pain of losing life to a system that does not care whether you live or die.

Protest across the country have brought light to issues when many mainstream media outlets have failed to feel the pulse of the people who are demanding change. During protests, many are inclined to carry a sign to convey a message or share something they feel needs to be addressed. Within the new generation of protesters, art has become an important medium to convey messages to the masses.

Coupled with protest, the lockdowns put in place due to COVID-19 presented challenges for many. In a world where technology rules and everyone is now working from home or attending school remotely, it was hard to ignore the movement for social justice taking place outside. Social media would ensure that was the case. And though it was good that a lot more people were forced to pay attention because of the surrounding circumstances of the world, for those who are all too familiar with the pain of being black in America, it was hard to take in all of the news without it taking a mental toll.

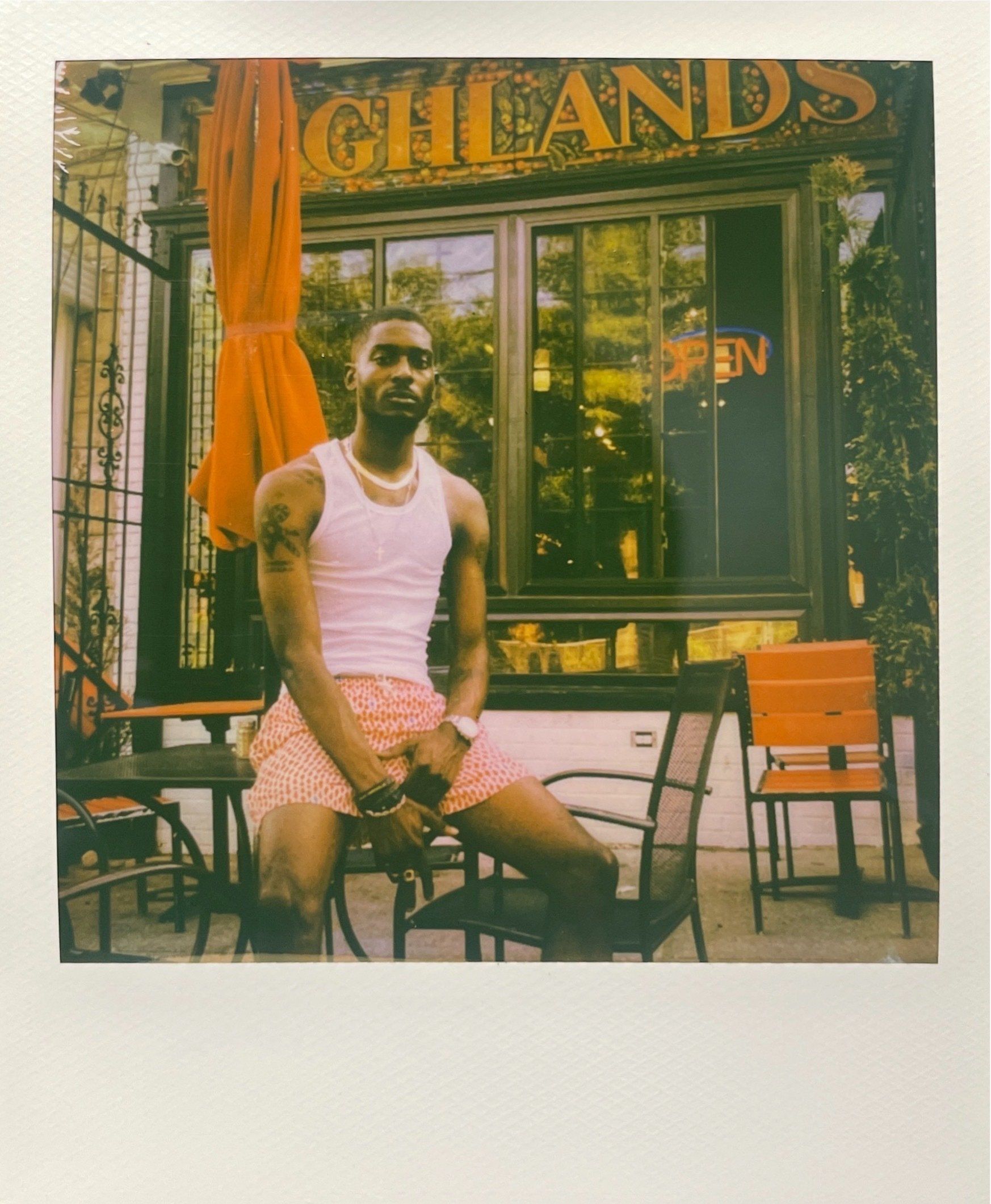

For DC born and raised artist Yaytunde, art has been a major outlet during this tumulus year. A true chance to make a statement, while also addressing the many emotions that the death of black people wakens.

“I was inside a lot obviously, and I think at one point, my screen time on my phone was like 21 hours a day. It was insane. I was like this is just not healthy, but I was just taking in all the news.”

Yaytunde’s sentiments are felt by many. The constant consumption of black trauma on social media is troubling, and may ultimately desensitize a generation of black youth to the death and brutality black people face in this country. Luckily for Yaytunde, the constant consumption translated to action.

“Everyday I was just like taking it all in; and it was really traumatic news too. I was having to process this on my own. But I also recognized that this is a time for a lot of change and I was like, I cannot just stay in the house and do this. So one day I woke up and I was like I'm going to go protest. “

Coincidentally, Yaytunde picked one of the most intense days of the summer protests in DC to join the fight. The President, trying to enforce his rhetoric of law and order and curb violence and destruction to buildings and statues in the city, unleashed the national guard on protestors into the streets of DC. Many were arrested. Rubber bullets were shot into crowds. And the national guard used several tactics to separate and stifle protests of any kind.

“It felt like I was in the purge, it was very overwhelming for me. There were loud explosive noises that were happening, and people just like running. In my mind, I was like I support people, but I can’t be out here and do this part, I had a friend get shot with rubber bullets.”

The events that took place during her first night of joining protests lead to some critical thinking. What would be the most effective way to spread a message, support protestors, without being caught in the direct crossfires of the chaos. She found the answer around her, on the now boarded walls of DC.

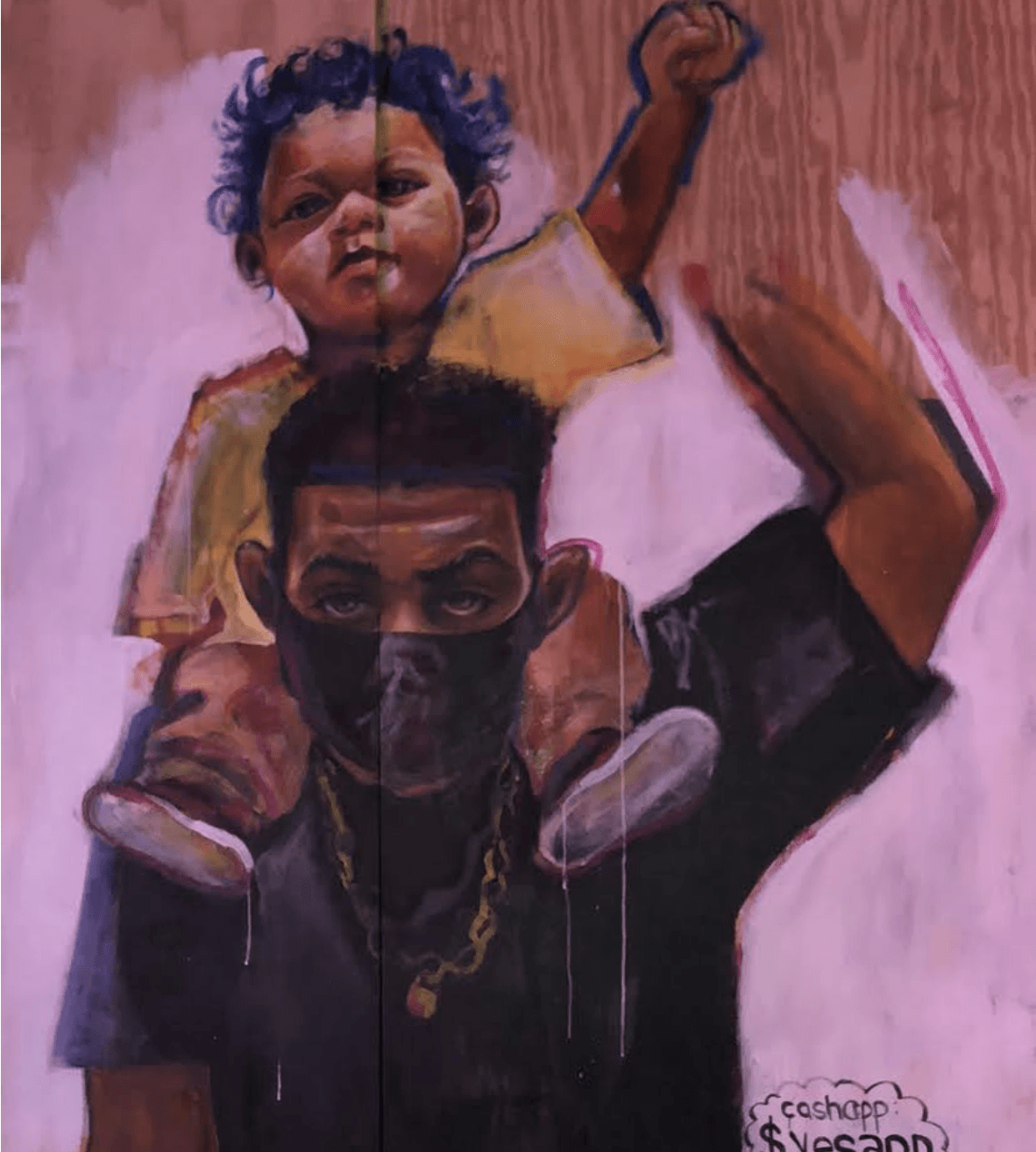

“I noticed there were so many boards, everywhere for blocks and blocks, and this was around the White House in D.C I was like these are basically empty canvases essentially.”

After noticing many people painting on canvases in downtown DC, she reached out to someone she saw painting about how she could participate. After submitting previous work addressing police violence to the group, they asked if she could turn in something different. This rubbed Yaytunde in the wrong direction. Who were they to police how she should express her grief. It was then that she decided to work alone, and spread her own message upon canvases,

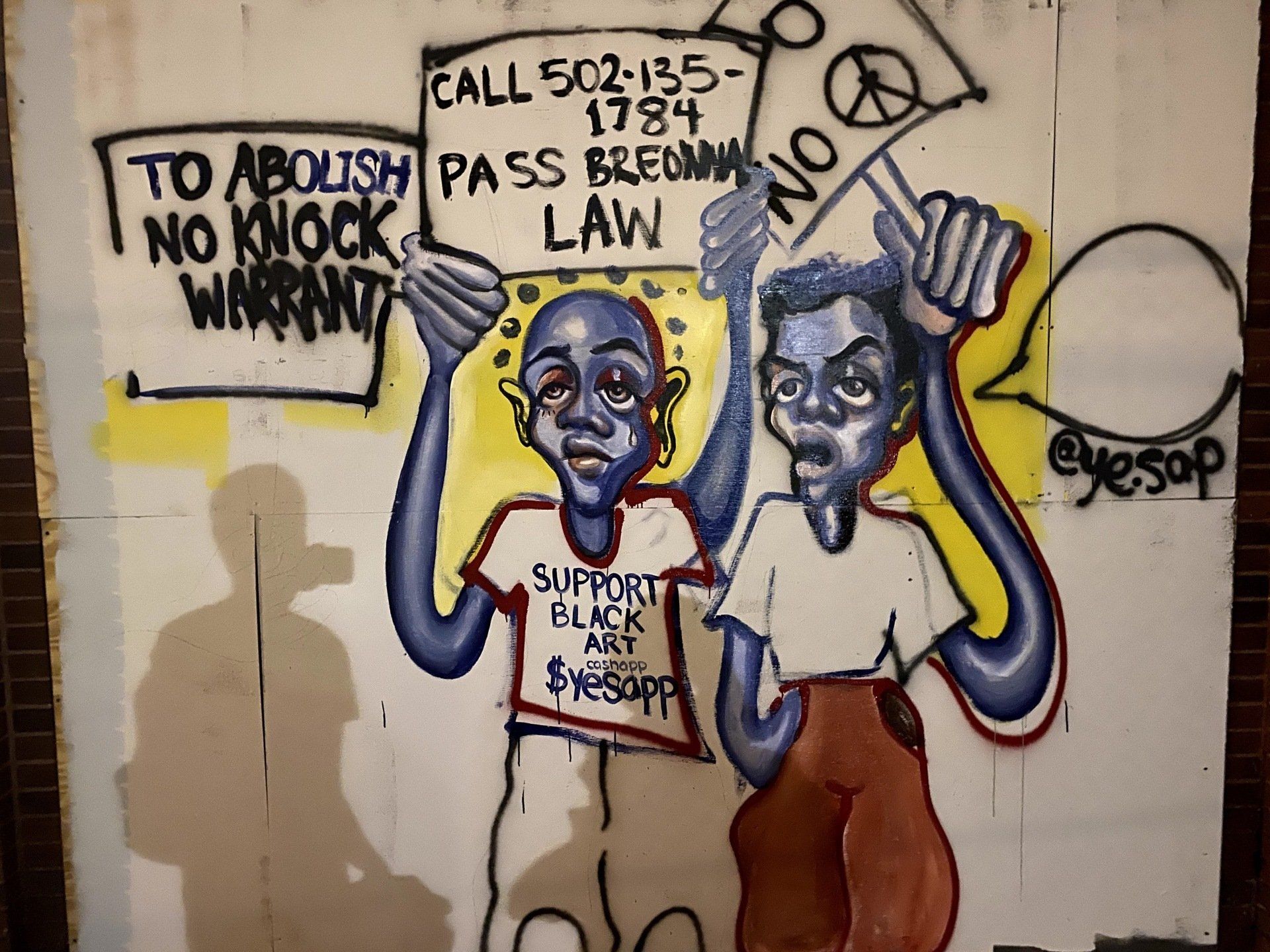

“There were still things that needed to be addressed. Still things happening, and the art being put up, it was nice but it was the kind of cliché unity pieces that people have been talking about for years. So I was like okay, I'm just going to do it myself. Like, why am I asking permission from a white person to do black lives matter art or art for black lives? I saw this thing online and that was like, if you carry a ladder around nobody asks you questions. So I just grabbed the ladder from my basement and took some paints and set up a wall. This is the night before Breonna Taylor's no knock warrant (law) was going to be passed, so I felt like the bulletin board or the plywood, would just be a way to get information to the public because I know that on my Instagram timeline, there's a lot of people who are obviously advocating for social justice or all preaching to the choir. Everyone that I follow is circulating the same information to each other. And it's like, we're not the ones who need to see it. I mean, I understand that we might be a network, so we spread to people who do need to see it, but it was just like, this is the same information being circulated to the same kind of groups.”

“As public art, anybody who would pass the White House, or those very corporate places would see it. So I did my first mural and it was like images of these random protestors and they’re holding up signs, and in the signs I put the number to call for the Breonna Taylor case and what to say in order for the to pass the no knock warrant law.”

“That was the first piece that I did. Part of it was kind of relieving to not attach like social media to it. because it's just like whoever sees it sees it, like, you're not worried about that. It’s not for any kind of personal attention, but while I was out there and painting, people would stop and ask questions, which was really interesting because a lot of them actually didn't know what was happening in that sense, which I found interesting because just being online, you just assume that everyone is.”

With her dynamic art style, Yaytunde’s art gained many admirers. Those who passed by would often take pictures to tag on Instagram or call the numbers or donate to the initiatives she highlighted within her work. On the flip side, some of the pieces did draw Ire.

“One day I actually went out to paint with my mom. A group of cops came up and one had said nice art and asked if I had been working on this before today, and I was like yeah. Then another came up and asked a similar question and I was like okay, what is going on? And my mom actually said it looked like he was going to cry. And the officer was like, I’m sorry to have do this, but someone reported that you had guns, I’m going to need to check your bags. And he was just like I’m so sorry, it’s my job and I have to search for safety reasons. That kind of scared me a little bit because who would tell the police we had guns?”

Despite her brief interaction with law enforcement, Yaytunde found her outlet, her way to contribute to the movement and voice her concerns.

“It was also a way for me to get my frustration out at the time, and just like leave it in that space. So that gave me the opportunity to process everything that was taking place.”

Though she was able to find a positive outlet, she still had a lot on her mind, especially in regard to Breonna Taylor.

“I haven’t posted this one yet though because it just felt weird how often I was seeing her named used in different places for different reasons After a while I was like, I don't even know anymore what justice would look like for her. A lot of what people were saying was to abolish this system, abolish police, abolish just everything and for people to say arrest the cops in the same breath just seems like we're trying to put them in the same system you’re saying is flawed. So, what's the real solution?”

“It just became like a punchline, you know. It was just like, Hey, I'm at the beach, also arrest the cops who killed Breonna Taylor and just became like, do you even know what you're saying anymore? Because it's a contradiction. And it just kept being in the news.”

As the weeks went on in the summer, many of Yaytunde’s pieces were ultimately removed or painted over. DC has tried to make a transition back into a normal state removing boards off of many of the businesses. Yaytunde however, was not discouraged by the arts removal.

“I painted it, knowing, that it’s temporary. It would be seen when it was seen. I wasn’t painting it to keep it. Its purpose was to inform, to be there in the moment for protestors.”

Yaytunde, like so many other black women, channeled the many emotions she felt into something that would help and ultimately uplift others. In 2020, it has been common for people to be absorbed with everything taking place, especially in the era of COVID, with our definition of what’s ‘normal’ currently being redefined. As we continue to live in America, many of the injustices that black people face will not disappear. It is important that we all find our process for grieving, and how to channel the emotions that grief brings into the change we would like to see.