Artist Spotlight - 93 Bandits

#floodthemarket

Alright, so we're here with the 93 Bandits. The first question we're going to start out with is how did 93 Bandits form?

Grizz : We started in like 2015/2016. I can't remember.

Rashad Stark : I want to say, it might've been 2015, late 2014.

G : Alright, so we were in this group, right? And nobody was dropping music except for me and Rashad. So we said hey, we should like break off into groups of two and drop individual EPs. Me and Rashad were going to make a joint and everybody else was going to make a joint. You know what I'm saying? So I remember I hit these niggas one day as I was going to work. I used to work at Best Buy. I'm like “Yo man, give me some ideas for the designs of these shirts, man”. And the niggas, I’ll never forget this shit - it broke my heart - said, “You can't design everything for everybody. Everybody's image is different.” I'm like, well I'm trying, you know? A couple of weeks pass and then we decided to break up. All love. So I’m headed to this b* house and I hit Rashad, I have this random ass idea. I'm like, “Yo, you want to start a group? Me and you, like a duo.” He's like, “I could see that happening.” I remember we had this song when we first started rapping, right? It's called Bandit Life and I was like “Wow, 93 Bandits. We’re both born in 93. That'd be a wave.” So after that we just kinda started planning on what we were going to do next. That was in like 2016. We had a little run, this little three song run we did. A lot performing and shit. Then we fell back to really hone and revise how we were going about the group because it was just two of us. It was a lot of niggas that had like eight, nine people in groups and shit. We just felt like we were boxing the whole rack of niggas with just two of us, you know. So that's where we are now. This rebuilding stage or rebrand. You got anything to add, nigga? *laughs*

RS : I just felt like everybody in the old group wanted different things and they were blaming it on the brand. It just got to a point where people felt frustrated and everybody wanted to go their separate ways. But it didn't really make sense for me and Grizz to not keep making music-

G : -because we got good chemistry.

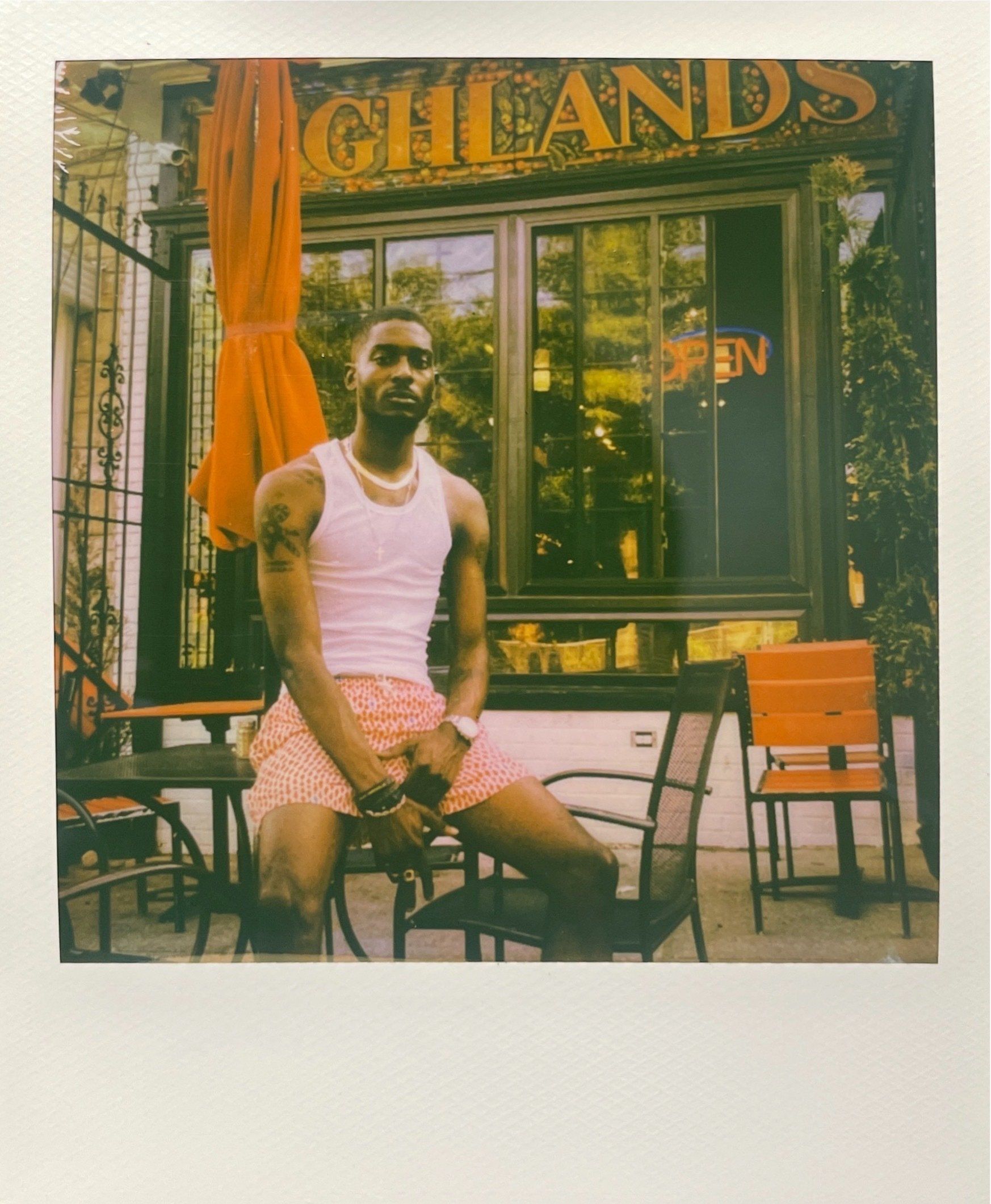

So, we’re here with Rashad Stark & Grizz (Grizz on 13th, Steezy Grizzlies)… how do you all get your names?

RS : So, Grizz actually helped me determine my name. Back in the day, I had a name.

G : *laughs* What was your name?

RS : It was DLo The Hero. Eventually, I felt I needed to change that, you know what I'm saying? For my image, for my brand - I need to have a more serious name. So people can get on that, whether you fuck with the music or not. I don't know how many people really want to support a nigga named DLo The Hero. But I wanted to still stay true to myself, so I was going to stick to the origin of my original name. So it was between two: DLo Parker & Rashad Stark. One of them still sounded corny, so I already knew which one I wanted to go with. Spiderman is my favorite superhero. Iron Man. It's my second favorite, so I was like, I can go with that… sounds sexy, you know, like I'm like a porn star. So that's how that came to be. And Rashad is my middle name.

G : I just changed my name again. So its just Grizz. The Grizz on 13th is just for Googling purposes because if you Google “Grizz”, the fucking Memphis basketball mascot is called Grizz too. So it's really just Grizz. How I got the first rap name Steezy Grizzlies - I was smacked one day and I was watching Animal Planet. Matter of fact, my rap name when I first started was Steezy Snapback. I was in AP Bio and my man Danny, Daniel West, was like, “Oh, you can rap? But that's a shitty ass name.” *laughs* He was like, “The ‘Steezy’ part tight, but you gotta change that ending.” And this is when Curren$y was popping and I was on that smoking wave or whatever. So I was smoking, watching Animal Planet. Motherfucking grizzly bear popped on the joint and it was like the European niggas that be talking like *uses British accent* “The grizzly bear as he stalks his prey.” Just talking about him and, basically, saying how the bear is real peaceful but he could turn up too. So I was like, that's literally me, right? I recently changed it because I outgrew it. I'm not really “steezy” anymore, per se. As an artist, that name had a lot of growing pains. I had to learn a lot, trial and error, a lot of tapes. That was shit that came under that name. The new name represents moving forward.

What was your first real introduction to hip-hop?

G : I remember, man, I used to hang out with a lot of thieves.

So there’s a backstory to the “Bandit” part of the name, like shit *laughs*

G : Shit. redacted used to steal! Him and redacted . They came up off Target, hella CDs: 50 Cent’s Get Rich or Die Tryin’, Mobb Deep’s Blood Money , Lloyd Bank’s The Hunger for More . We were G-Unit stans. I was the only nigga that had a computer, so I’d burn CDs and then sell them at school. So that's how it was in middle school. Then I went to go visit my grandma in Chicago and my aunt had a random ass Kanye CD, The College Dropout . For a whole summer, I played nothing but The College Dropout everyday, bro. Everyday. Everyday for like six, seven hours, I'd be like on AIM, the lil AOL joint. Rapping to random white bitches, bumping Kanye West. Like “Age, Sex, Location. Yeah, I'm listening to Kanye West.” The whole CD is pink too! I was like “Damn.” It's just so tight. So I kind of had the contrast between gangster shit because I used to hang out with nothing but hoodlums. But Ye was off some different shit that I related to more. And then through Kanye, I found Pharrell and Talib and, surprisingly, Jay-Z. That's my first experience,

RS : I wasn't honestly - I'm kind of ashamed to even say it, man - I wasn't really into hip-hop like that when I first started out. I was more of a poet. At the time, I was in high school, in 11th grade and I won this poetry contest, got some good bread and that kind of streamlined into me freestyling and shit. But I would only freestyle big wild shit! Make niggas laugh at the lunch table and shit. So by the time I hit 12th grade, I just had an epiphany in class. I was just like, “Yo, I ain't got shit moe, like b* is cheerleaders, niggas is on the football team, niggas in engineering winning motherfucking contests in robotics.” I was like, I don't do shit. But I'm a poet. Let me see if I can streamline it into rap and I just ended up getting into it. I was in my motherfucking attic, make an iPod mixtapes, dropping them on DatPiff. I remember thought I was doing something man. I had one joint called, it was a Christmas project called The Naughty List , and my friends would support me. This is when everybody was on Twitter. And someone tweeted “I don’t know who this is… but you need to let him know he’s garbage.” And I was just like “Damn.” Let me really buckled down and see if I’m so shit, because I really didn’t know. So I started listening to more artists, more rappers. Probably whoever else was out. Then I heard Big Sean and I just like, “Okay, hold on.” I'm talking about mixtape Big Sean. I felt like he was a huge influence on me. I'm listening to him and I feel like he wasn't super like hip-hop, like super boom bap-ish. I was able to identify and fuck with it and be like, I can understand why this is practically good rapping. So I adapted the flow and I started doing that. Fast forward and I'm slowly but surely doing more and more researching and being more comfortable with my shit. Boom. We started going to Everlasting Life Cafe down on Georgia Avenue and that's when I was around some crazy niggas who knew how to rap, like Sir E.U., that nigga is amazing. I’m talking about they were RAPPING and people were resonating with it and all I could think was, “Yo, this is crazy.” And so I studied those niggas. Like, what the fuck are these niggas doing? Why do niggas think what they did was so tight and why are people captivated by it? I started to see: repetition, metaphors, similes. Really studying the vocabulary. Just trying to get into what really makes a rapper a good rapper. I had to like find my love of hip-hop in the midst of me trying to get better.

G : Back then, I think we actually rapped more than we do now.

RS : Oh, we most definitely did.

G : Because I remember how I would write a verse everyday, just because I was trying to be

better than them. But cookies crumble and bitches mumble. You know what I'm saying?

RS : It’s a new era.

In relation to that, and I think this perfectly rolls into what you guys were just saying at the very end - Do you guys believe that the presentation or the project itself is more important in this day and age?

RS : Presentation.

G : Presentation. Niggas is stupid. Majority likes the presentation. The gatekeepers like both.

RS : If you present something good enough, you can trick people into thinking that something is what it's not when it comes to a product. Whatever an artist decides to put together.

G : It's like buying Fiji water and shit. Fiji, it's just regular water but the bottle looks better. I know a lot of niggas buy the bottle.

RS : And they'll convince themselves, “Damn, this shit tastes cleaner! It be colder when you take it out the fridge! That shit blue!.”

G : Perfect metaphor for rap right now. Big ass bottle of Fiji water.

Putting on it in the context, what's your creative process as individual artists and as a group?

G : This is wild because I recently just changed mine, like as of May. I used to be really meticulous and take like three or four months to make a song because of everybody I'm around. I wanted to make sure the product was so perfect. Now? I hear a beat and if I resonate with it, I try and make the song as fast as possible. Get my ideas, the product and idea, just put it on wax so I can listen to it over and over again. And then I make my improvements after that. Because I'm starting to believe perfection with anything is ji impossible. And people want product. A lot of times niggas got stuck on the perfection of it. Fuck that shit, man. Whatever you produce to the world is what you’re gonna produce and it's gonna get better over time. As long as you keep in mind that you want to get better. So I just try to do shit as quick as possible and not get stuck on a song or stuck on a project. Keep it moving. I'm at the point in my skill now where I'm not making some shit. I'm just trying to get that to the point where everything I make is good. And then, eventually, where everything I make is great.

RS : Honestly, and I'm a bit ashamed, I normally just get drunk as shit and eventually just create. Like literally, when I dropped The Most Lit and The Most Lit 2 , I only recorded when I was drunk. I would get all my inspiration when I was drunk and off the drugs. Especially when I was drunk and off the drugs at the same time, but that’s just me. I can't even explain why it worked, but it did and my best stuff will come out of it. But I don't really have any rituals or anything like that. I'm always thinking of music. My projects, I never have a concept in mind for the most part, I'm always just making shit. Then the music speaks to me. If I make seven, eight songs, I know where my energy is and it feels like I don't even have to focus on it. And then it comes together as genuine as possible, when it just feels right.

G : That’s the thing about this nigga. Even if he feels “Eh” about a song, he’ll have enough confidence to put it out, like "Fuck it.” It'll be the song he doesn't even like the most. But everybody will fuck with it. How many times has that happened before? I’ll say a word wrong. And he will be like “Nah, it's good.” And, it's good. We'll put it out and niggas will geek over it and eventually, I’ll forget what the fuck I was even worried about with song.

That almost goes back to what you had just previously said about your process, about not being as meticulous with it and just getting your ideas on wax. Especially, I think, with people's attention span in music nowadays

G : I don't want anybody who reads this shit to be like I’m off some one & done shit in the booth. I’m off some rap a song, send it to these niggas (the rest of the 93 Bandits team), get their feedback. Maybe I could do this better or that better, but I'm not really about to be like, let me sit down and analyze the metaphor and the context of the similes that I have to put together to create this lyrical masterpiece.

RS : I feel like the reason we as artists are even like that nowadays is the business aspect of it. Once upon a time, I used to be extremely meticulous.

G : Nobody gives a fuck, that’s the sad part.

RS : You really just got to ask yourself what matters. Like for instance, I could have recorded any of my last projects in a professional studio. Does my music deserve that? Sure. Do I have all the resources to make it happen? Possibly. But at the end of the day, for me, it always stems back to creating. Picasso made paintings. Niggas probably sounded dumb as shit going to Picasso like, “Hey bro, you might want to put one more splat on that.” But then after he started getting that bread, it's like, what are you going to say? It's a different type of thing because when you’re making music for other people and the masses, first of all, they can't fucking identify most of the shit that goes into almost any of it for real, for real. It can be frustrating. There is always more music to make, but most definitely. If we got some shit that we know deserves to be taken time on or being really meticulous about bars, etc, we do take that time. But generally we don't stress about it.

You guys are MCs but you also deal with the production side of things. Who is the best producer in hip-hop, all-time, but then also your favorite current guy doing his thing on the boards?

G : Pharrell is the greatest producer of all time. Anybody could fight me over it. Pharrell Williams. I don’t think anybody can argue with that nigga’s catalogue.

RS : Yeah, I don’t have anything to say. *laughs* I would say Timbaland is up there as well.

G : But who's my favorite producer now? It’s between Tay Keith and Pi’erre Bourne.

RS : My favorite producer out right now is Yung Kifo. My little bro.

G : Oh shit! I feel like an ass. He’s the next Metro Boomin’, I’m telling y’all.

RS : I swear to God, that nigga just be in his room for like days.

G : He's 17. He’s in Colorado.

RS : He just trying to trap it out till he can get the fuck. That nigga don't even have the full version of FL. So that means that nigga has to crank them joints out. The mixes are clean. He's not going back to tweak anything.

G : He can't tweak anything. Remember when he just sent us his recent beats because he wanted to put his tag in it? I think he had to remake the whole beat just to put his tag in it. He’s only 17. He going to be the best, I’m trying to tell you.

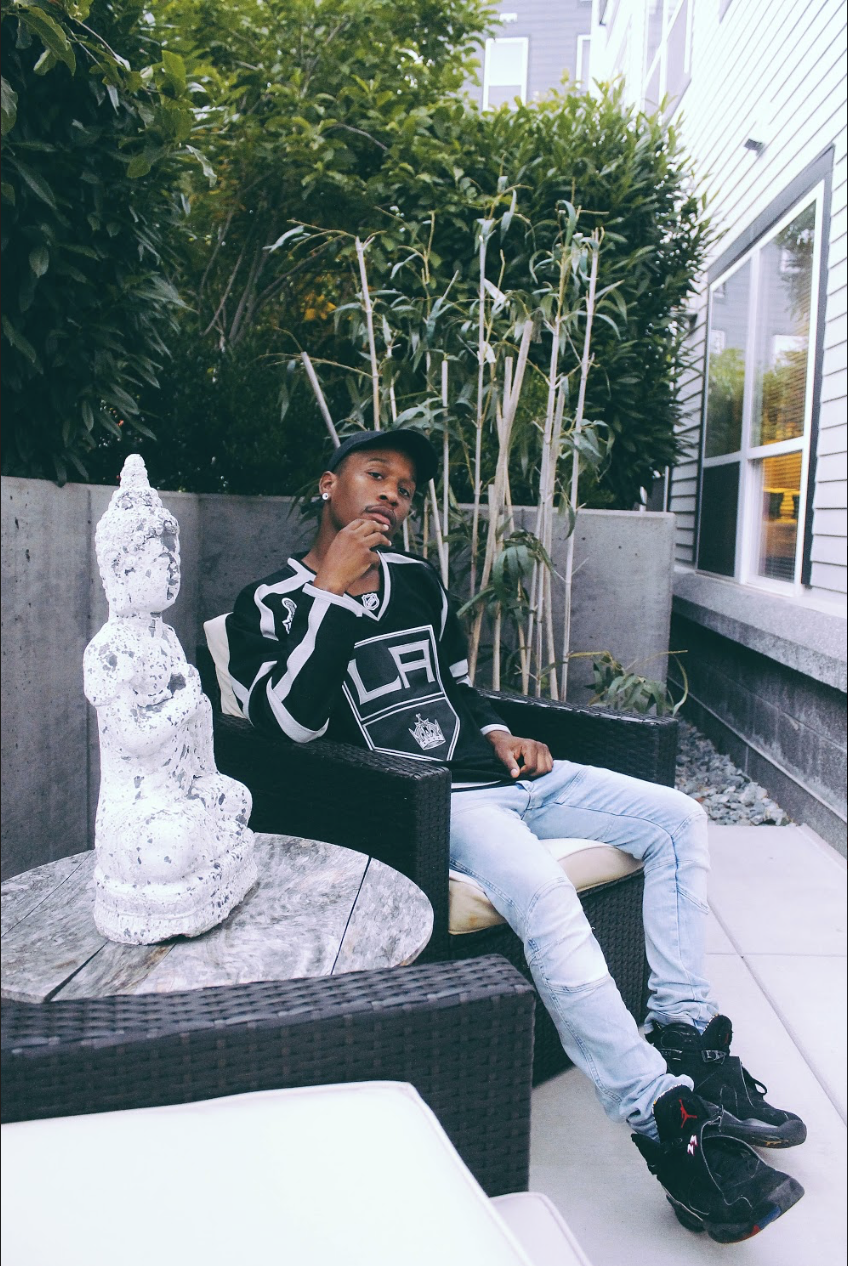

So speaking on that, who are the members of 93 Bandits as a collective and what are their roles?

RS : Since we started off as a rap group, the first people who come to mind are always the artists. So first, it's me, Grizz and Hooks Ventura, as far as artists who have catalogues. We also have Ian Sadiqq, the PACE man. Yung Kifo, young producing genius, the prodigy. Pine Roasted, our DJ. We got Monty, manager/brand ambassador. And big VP, Farid. Lastly, we got Najee.

In your opinion, how does 93 Bandits differ from other collectives in the area?

G : Well, for one thing, I feel like we actually enjoy what the fuck we’re doing. It's like a lot of collectives, musically, are so worried about getting on, that there’s a level of desperation when I look at their product. Like, “Yeah, nigga. I’m from the mud.” Well, aite nigga. None of us are stacking. So you have to enjoy what you do. We make music we like and we enjoy. I hope people enjoy it. I feel like niggas make shit for other people all of the time. So I feel like if you do fuck with 93, you investing in a genuine brand of person. It's like having good product with good personalities. That’s our main appeal. Just regular niggas that do tight shit and you can do tight shit, too. I'm able to do it. If you're not, you can just get on the bandwagon and watch us do it.

RS : In being realistic, we have a lot of collectives in the city. I feel like when it comes to us, it's the energy and the vibe. Especially with the way we're expanding. There is so much stuff we want to do and it's not even just music based anymore. It's not just about who can rap or who can make a beat, you know what I'm saying? I like to think that the collective is a family that wants to strive and push quality.

G : It’s just a lot that’s wrong. The product be wrong, man. The ambition be wrong.

What was the thought process behind 93 Week?

G : So niggas always do a week where their collective drops music and, while that's tight, it's not different. I want to create experiences for people, more so than just music. So, let’s do shit outside of music to create hype around the music in order to hip people who know us socially to our music and vice versa. A lot of rap niggas, people don't really like them in person and that's not the case for us. We make good music and people like us personally. Hopefully. *laughs* So I don't like. Yeah. So we just created the experience for Niggas bath hundred percent, hundred percent. That was the whole idea behind the joint.

Where do you see the 93 collective in 5 years?

RS : I want to keep it a stack, man. It might sound backwards, but I personally don't even necessarily have a vision of where I want it to be yet. I'm a firm believer in having faith and having faith in hard work and you never know what can come out of it. Of course, there are a lot of like typical accolades I would like to reach, but for the most part I really just want to see where the brand can go with the amount of passion and hard work that I know we're going to put in. Five years is a long time. So if niggas is doing what they're supposed to, we might end up in places we don't even imagine, that we didn't set out to be.

G : I’m trying to make the 93 apparel like the next OFF-WHITE. Also, I want to eventually have an imprint under a major label. 93 Bandits Records. But my biggest thing bro, a lot of times this might sound like real cliche, but I'm not really doing it just for me. I’m trying to do it for everybody who I think is a creative genius.